Guest Blog Post – Yoga and/or AI: How AI marking can improve staff wellbeing

A guest blog post for The Edtech Podcast by Rebecca Mace, Founding Partner at Human Digital Thinking and written for Progressay | Twitter: @beki_mace; @Progressay1

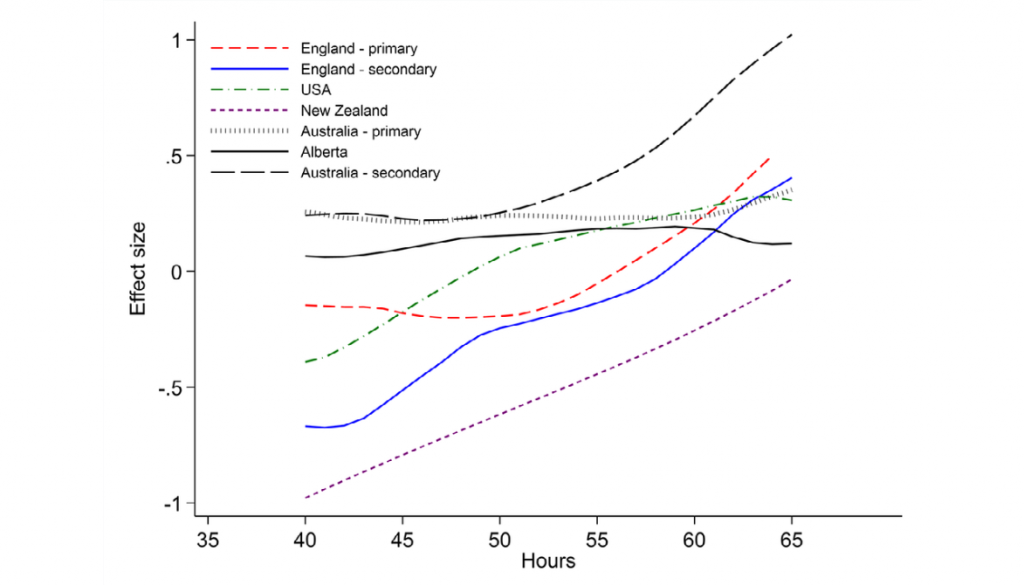

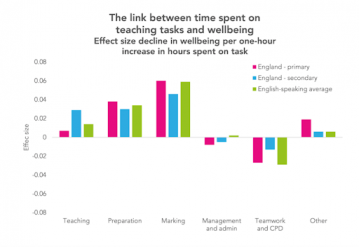

Unsurprisingly, research finds that teachers are dissatisfied with their workload, however, it has also thrown light on specific aspects of their working day and emphasises that certain aspects of workload are viewed more negatively than others. In particular, the growing demands of assessment, marking and data entry, often in order to comply with (perceived) demands of accountability systems have proved to be particularly unpopular with teachers. With increased tracking of students, more quantifiable elements of a pupil’s education are required in order to measure “success”. This usually translates into more marking for the teachers.

[T]ime that teachers spend marking is the key driver of workload stress and poor levels of workplace wellbeing. […]”.

Almost a quarter of full-time secondary teachers in England currently spend a minimum of ten hours per week on marking, often more. Marking appears to be the thing that causes the biggest decline in wellbeing, closely followed by lesson planning.

https://ffteducationdatalab.org.uk/2020/11/how-are-teachers-working-hours-linked-to-wellbeing/

It seems an easy fix would simply be to stop! But marking being the main cause of poor teacher wellbeing runs parallel with an educational narrative that extolls the benefits of feedback on student attainment. And, for many the term “Feedback” runs hand in hand with marking. As such, improved feedback for students can end up with many teachers feeling an additional burden. It seems like teachers are stuck between a rock and a hard place.

However, major exam boards have been running trials in schools to see if using Artificially Intelligent marking systems, using Natural Language Processing, for essay subjects like GCSE English Literature, is a viable option. The schools involved have talked about the process of providing incredibly high quality and individualised feedback on individual students, as well as giving the teachers insight into class-wide problems. The final clincher was that it did all of that in less than half the time it took a human to mark an essay.

The teachers trialled reported it took them roughly 12 minutes to mark an essay by hand. The AI can do it in 5 minutes. Imagine you have a class of 28 students: 12×28 = 336mins (roughly 5 ½ hours). It only took the AI 2 hrs 20m. Although this is an overall time saving of around 3 hours, it is important to remember that it does not take very long to upload the essays and then the teacher is free to get on and do something else – so it actually saves the teacher the entire 5 ½ hours. And that’s just one class. Imagine that multiplied out over all of the classes they teach.

Although many initially expressed concern over the system not being able to pick up on nuances of language or perhaps creating a system that could be gamed by users, this quickly proved not to be the case. The schools surveyed stated that the feedback the system was able to provide was incredibly detailed – both on an individual student level as well as a whole class level. This enabled teachers to work on iterative feedback and targeted interventions with specific people or subgroups, as well as impacting upon their whole class planning.

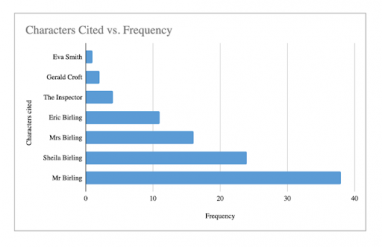

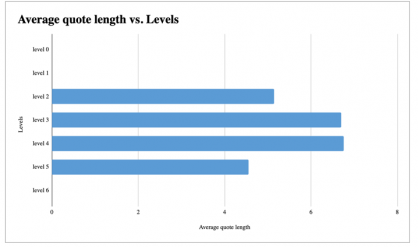

Examples taken from An Inspector Calls GCSE past paper question.

The first example could highlight gaps in pupils’ knowledge – in this example the class clearly all know about Mr Birling but Eva Smith features hardly at all. Sometimes the data can be used to demonstrate that less is sometimes more – for example the second chart shows that the longer quotes do not result in the highest grades!

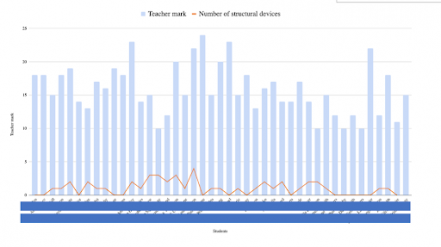

The graph below plots individual students (anonymised) against the teacher mark and the number of structural devices. This insight is something that the teacher can then use to inform on lesson planning.

In short, this technology seems to be offering both teachers and students a win-win situation. Teachers are having their time freed up to do other things – be that planning or parents meeting or even attending the staff wellbeing yoga sessions on offer! – as well as being offered greater insight into their students work that they can build on with excellent quality feedback.

References:

Allen, R.; Benhenda, A.; Jerrim, J. and Sims, S. 2019. New evidence on teachers’ working hours in England. An empirical analysis of four datasets.

Bradbury, A., & Roberts-Holmes, G. (2018). The datafication of primary and early years education: Playing with numbers. Routledge.

Cooper-Gibson Research. 2018. Factors affecting teacher retention: qualitative investigation. Department for Education Research Report. Accessed 27/08/2019 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachme nt_data/file/686947/Factors_affecting_teacher_retention_- _qualitative_investigation.pdf

Department of Education [DfE] (2019). Teacher recruitment and retention strategy. Accessed 27/01/20 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachme nt_data/file/786856/DFE_Teacher_Retention_Strategy_Report.pdf

Foster, D. 2019. Teacher recruitment and retention in England. House of Commons briefing paper 7222. Accessed 17/07/2019 from https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7222/CBP-7222.pdf

Jerrim, J., & Sims, S. 2019. The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018. London: Department for Education

Jerrim, J. and Sims, S. 2020. Teacher workload and well-being. New international evidence from the OECD TALIS study. Working_Paper_Workload_Wellbeing_November_2020

Perryman, J. and Calvert, G. 2019. What motivates people to teach, and why do they leave? Accountability, performativity and teacher retention British Journal of Educational Studies DOI: 10.1080/00071005.2019.1589417

Selwyn, N., Nemorin, S., & Johnson, N. (2017). High-tech, hard work: An investigation of teachers’ work in the digital age. Learning, Media and Technology, 42(4), 390-405.